Imagine the following scenario. You go to see your doctor for your annual physical. You get bloodwork done. She calls you the next week: “Your lab numbers are way below where they should be. I’m concerned about your health …”

Click.

She hangs up. That’s it. No other information. No details or explanations for why the numbers are so low. And no next steps. No guidance on what you should be doing to bring the numbers up to improve your health. I know, it sounds crazy. And yet that’s the metaphorical equivalent to how Net Promoter Score (NPS) works. You ask your customers to give you a rating of advocacy. You, in turn, get a single number back, akin to getting that jarring phone call from the good doctor: “I’m concerned about your (brand) health” is all you’re left with, as you are left stranded on the line scratching your head about what your failing NPS score means, and what to do about it.

Such a puzzling situation should give any decent marketing manager a great deal of anxiety. But it doesn’t.

Or maybe it does for you. But despite knowing deep down that there’s something terribly wrong with the misguided metric, you go on using NPS because i) everyone else does (including your managers and clients) and/or ii) you are not sure what else to use (and something is better than nothing, right?!)

We Have Come to Over-Rely on NPS

Over the last couple of decades, NPS went from a budding idea to an overgrown weed. It’s crept into every nook and cranny of marketing strategy (and, more recently, people/HR strategy). Just look at the Google trends for NPS search terms to see its growth, especially in the last 5-7 years. Unfortunately, the herd mentality of the marketing world created an addiction to a misguided metric that took hold. Heck, even the creator of NPS himself sees the error in our ways: “As its popularity grew, NPS started to be gamed and misused in ways that hurt its credibility.”

Fortune 500 CEOs embed the notorious score in their management dashboards. Some check it every board meeting – sometimes first thing every morning. As Michelle Peluso from IBM comments, “It’s more than a metric. One could use the word ‘religion'”.

As its popularity grew, NPS started to be gamed and misused in ways that hurt its credibility.

The cultish fixation on NPS in the highest offices is worrisome, to say the least. The last thing we want our business metrics to be is ‘religious.’ Our recommendation? Save your Hail Marys for Sunday mass and last-ditch football passes.

Remember the 7 Deadly Sins of NPS.

Deadly Sin #1

NPS as a Number on Its Own Means Nothing

NPS has two arbitrary anchor points (-100 to +100) that are arrived at through the even more arbitrary calculation of the percent difference between promoters and detractors (forget the passives – who cares about them!). It demonstrates the randomness of numbers.

On their own, numbers are arbitrary. They only add meaning when they become attached to something in the real world.

We, humans, are the ones who have to attach importance to them and, thereby, make them understandable and ready for real-life action. Let’s take the example of Celsius versus Fahrenheit. Both sets of numbers do the same thing – record temperature. But celsius is the far more ‘meaningful’ metric because the numbers’ work for us’ in the real world. They’re tied to something in our direct experience, namely the properties of water. At 0 degrees, water freezes. At 100 degrees, water boils.

It goes even deeper than that. We have skills of numeracy encoded in the brain because, evolutionarily speaking, it was – and still is – adaptive for surviving the harshness of reality.

Not because our ancestors were scrawling calculus formulas on cave walls but because numbers helped us to make sense of the world around us and to share relevant experiences with others. “How many berry bushes should we forage? How many predator footprints did we just count back there in the mud?”

NPS doesn’t carry inherent meaning and can, therefore, ‘mean’ something different for different people. In a recent client project, we saw an NPS of 67. One person on the team raved at the number, “I’m so happy to see such a high score!” while the other sent a stern email inquiring “About the abysmally low NPS.”

What is 67 as a number? On its own, nothing. It needs to be brought to life.

Deadly Sin #2

NPS Tells You Nothing About What to Do Next

Remember the oft-used Peter Drucker quote? The one that says, “If you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it.” We should amend it to say, “If you can measure it using NPS, you still can’t improve it.”

If you’re the analytic type and curious about what’s behind your NPS, the best you get is a proportion of respondents who fall under the three categories: detractors, passives, and promoters. So what do you do with the so-called knowledge that XX% of people rated you a 7 or 8 on a scale of 1-10? Not much, I’m afraid.

If you can measure it using NPS, you still can't improve it

You’re left with more questions than answers regarding what to do next: Why did so many of my customers score us an eight instead of a 9? Who are they? Are they motivated to buy? Will they purchase again? How loyal are they to our brand? And what can I do to create more 9s and 10s out of these 8s?

In an ideal world, KPIs and metrics serve a direct future-oriented purpose because they give us information on what to do next.

“The number is X today, but if you intervene and apply technique 123, then that number will increase to Y tomorrow.” That’s what we want – a change to the score commensurate to some inputted action. You know, basic cause and effect

Imagine, for a second, that you need to boil water to make your (screaming) infant’s formula. Like an unhappy client crying for something to be done, the situation with your baby is dire. You need to do something immediately to have a direct impact and thereby change the KPI (the temperature of water) so that you make your screaming client (baby) happy.

So, first, you boil the water to 100 degrees celsius to purify it. Direct heat under the kettle (cause) leads to boiled water (effect). Second, you submerge the bottle into a bowl of ice water (cause) to cool the freshly boiled water to a perfect lukewarm temperature (effect) for the baby to drink. The number (i.e., the water temperature in this case) goes where you need it to, when you need it to, to serve a direct purpose.

As an abstraction of reality, a number is useless if we don’t know how to directly and causally impact it in the future. As a strategist or researcher, you need to know, ideally with a degree of certainty, that a specific intervention will improve a score – and the reality of the business as a result.

Deadly Sin #3

A Changing NPS Gives You False Confidence (or False Panic)

This one picks things up from the previous point. Businesses will go up and down over time. Market forces will naturally fluctuate. So there’s a lot of ‘noise’ in the system, and though we can’t control most of it, we can at least account for the noise by measuring it.

NPS doesn’t do this. Instead, we stand back month over month, quarter over quarter, and watch as the score (randomly) climbs, falls, then rises again. And we convince ourselves that these changes are due to something we did (or didn’t do). The fallacy in our thinking is aptly captured by the common teaching, “correlation doesn’t equal causation.”

Here’s why it’s dangerous (and foolish). As those unaccounted-for market fluctuations do their thing, we’re also busy doing our thing: running campaigns and spending money hand over fist to execute the latest CX strategy. We do this with the hope, of course, that all the money and effort spent will have a direct impact on our NPS (see Deadly Sin #2 above).

But what you see in a changing NPS, intermixed in all that noise, is an indirect impact, at best, and at worst, a process of total random change, partly due to all the extraneous factors in the system that you don’t know about.

This plays out in two ways- first, with false confidence. Let’s say you run a year-long campaign because senior leaders have told you that this year’s NPS target number needs to be 20% higher than last year’s. So you do some big thinking. You spend some big money. And each time you look at your NPS with your fingers crossed, you’ll see an improvement. And lo and behold – It increased!

And now you have all the confidence in the world that the change was the direct result of your efforts when in reality, your NPS increased because of myriad external reasons, most of which you have no idea are behind the change. These might include competitor action, new entrants into the market, job market fluctuations, who knows.

The opposite is also foolish, false panic. This time, imagine that a decreased score follows your campaign efforts. With a pang of anxiety, you see the latest NPS plummet in the opposite direction. You conclude, “Our campaign backfired and made things worse!” And as a result, you pull the plug on the project. Or, worse yet, your bosses freeze your budget and demand an explanation. Welp.

Deadly Sin #4

An Unchanging NPS Gives You the Same Type of False Confidence/Panic

There’s just as much missing information in an unchanging NPS as in a changing NPS. Like in the above scenarios, whether it’s false confidence or false panic is determined by whether you need the score to increase (panic that the score has stayed at a relatively low point) or not to decrease (confidence that the score has remained at a relatively high point).

The nature of how NPS is calculated is greatly misleading because even though the number is staying the same, there’s a very good chance that, in reality, there’s a bunch of stuff that’s changing, including the perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors of your customers. But you have no idea because your NPS is staying the same. And you take that as a good sign.

Let’s look at an example of another number, calories. Let’s say that your optimal food intake for your new diet plan is 2,000 calories per day. That’s the number/score, so to speak, which you’re striving for and monitoring closely. Now, let’s imagine that you came across a supposed ‘diet hack’ which claims that all that matters for weight loss is the target calorie score – your 2,000 calories. The foods that contribute to the number are irrelevant. All you want is the unchanging calorie score day in and day out.

So you eat what you want when you want – just so long as you hit the 2,000 daily calories. You like this plan because it’s simple and easy to follow – a single number—no need to fuss over multiple moving parts.

Sound familiar? NPS, cough cough.

But a couple of weeks in, you’re starting to feel terrible. What gives? You read up on a few reputable blog sites about how nutrition actually works. You find that ‘the-one-number-to rule-them-all’ is misleading. What goes into the 2,000 calories is just as important as the calorie count for health and weight management. It’s not enough to strive for a single number/score. Underneath the unchanging 2,000 calories is a drastic change to your diet that reflects the unhealthy feeling: refined starchy sugars, bad fats, and processed foods.

Like the calorie score for the naive dieter, an unchanging NPS gives you false confidence that you’re doing everything right. After all, the number says so. That is until you look in the mirror and find that your business suffers from bloated costs and unhealthy margins.

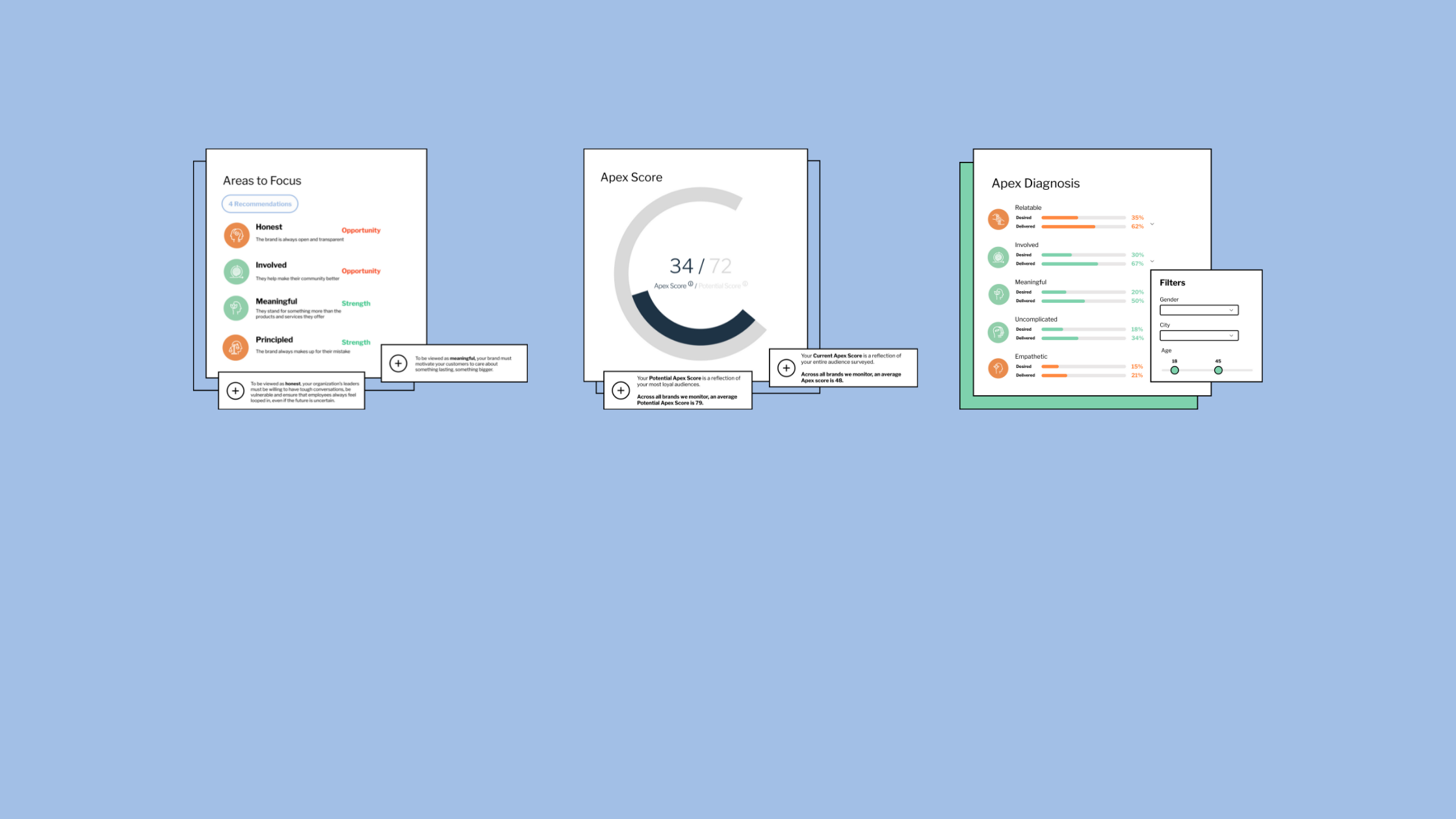

We had a recent client for whom this played out perfectly. Using our scoring system, Apex™, we tracked brand loyalty at two different times, one year apart. The number was nearly identical. If we were using NPS in this case, it would stop there. There’d be no further insights. The number hasn’t changed. Okay, onto the next thing on the to-do list.

Like the calorie score for the naive dieter, an unchanging NPS gives you false confidence that you're doing everything right.

But underneath the unchanging score was a critical insight: the composition of attitudes that make up the score had done a complete 180. At that point in time, the Apex score consisted mostly of rational attitudes.

But one year later, that (same) score consisted mainly of emotional attitudes. For this particular brand, this is what they wanted to see: the emotional connection driving loyalty for their customer base. We were able to reveal this insight and chart a course for their CX strategy. All this despite an unchanging score.

Deadly Sin #5

NPS Is Used to Justify Decisions After the Fact (and Is Making Bad Bosses Worse)

In the good old days, when authoritarian-style leadership was the norm, an organization’s most senior leaders (mostly old white men) managed people with tactics of top-down control. Before modern computation and digital technologies, many decisions were based on authority. Whoever was in charge had the final say, regardless of how sound their thinking was.

In the 90s, with the rise of evidence-based management and enhanced technology, access to information and knowledge meant that managers could make better decisions based on data, based on scores. Or, in this case, based on a single score.

There’s a catch, though. You know the saying, “Numbers don’t lie”? Not so. They lie all the time … if we want them to. Unfortunately, certain leaders in organizations will often hijack data and numbers to achieve their end goal. So, while some leadership ego has been removed from the workplace equation, there’s still a good dose of it out there (I know, shocking.) These subpar managers will decide on a whim or a gut hunch with an air of authority that they know best. But now, unlike before, bad bosses can slap a cheap veneer of data to make their decision-making look pretty when, in fact, the whole thing is rotted out from underneath.

In a word, data has a dark side. It can be misused, and with its allure of assumed authority, it can make bad managers even worse. NPS is the perfect number when somebody needs a quick-and-dirty data point to justify their decision. Everyone gets it, and nobody questions it.

Deadly Sin #6

NPS Takes the Focus Away from the Customer

This one is a natural consequence of Deadly Sin #4. So often, when a business metric gets misused and warped over some time, a funny thing happens. People forget about the original purpose of the number: to capture a reality of the changing business (and to improve the business as a result). In other words, it gets divorced from reality, and all you’re left with is a number.

As mentioned in Deadly Sin #1, a number removed from reality means nothing. An empty ‘vanity metric,’ NPS is perfectly suited for people to obsess over just the number itself, nothing else. The things that made NPS so attractive in the early days – ease and simplicity – are why it gets misused today.

Recently, a senior executive from a Fortune 50 company reached out to vent about his company’s use of NPS. “The score,” he says, “has been weaponized against certain leaders in the organization” on things that are totally unrelated to actually improving the customer experience.

With it being ‘just a number’ and nothing else, organizations will unknowingly try to attach that number to something else in the business to try and prove its value. The inventor of NPS recently remarked in a Harvard Business Review article that practitioners abuse it “by doing things like linking NPS to bonuses … caring more about their scores than about learning to better serve customers.”

If the creator of NPS is saying this, we should consider coming up with another solution.

Deadly Sin #7

NPS Is Based on Intention (to Advocate), Not About Purchasing Behaviors

NPS is a single question on the intent to recommend or advocate a brand/product. Unfortunately, decades of psychology research tell us that saying you will do something is not a reliable predictor of whether you will actually end up doing it.

People are terrible at basic introspection. We have an incredibly difficult time going inside our minds and creating a mental catalog with all the reasons to do or not do some future behavior. So more often than not, we just do it, and then we messily justify our intentions for why we did that thing only after the fact. It’s not as linear as we think.

There’s also the phenomenon of the ‘intention-action gap.’ In a whole host of life domains, including exercising, quitting smoking, eating healthy, and doing less Netflix binge-watching, we find ourselves making a plan to change our behavior (exercise twice a week), only to find that a couple of weeks later, we’ve not made it to the gym once. All this is despite the best intentions to improve our behavior.

For all the great products and services I’ve given a 9 or 10 on an NPS-style question, not once have I recommended them to a friend. I said I would. I never did.

Throwing Good Money After Bad

All signs point to us jumping ship on NPS. But we haven’t – and it’s been 20 years of throwing good money after bad. What gives? The sunk cost fallacy.

Sunk cost fallacy, a widespread cognitive bias, describes our tendency to follow through and to keep using something because we (or others) have invested time and effort into it, even though the current costs outweigh the benefits. That explains our irrational fixation with NPS.

It's been 20 years of throwing good money after bad. What gives? The sunk cost fallacy.

Big-name brands like Bain and Co and Qualtrics have attempted to revive NPS, hoping they can reinvent the ineffective metric to improve it. This includes taking the S in NPS and swapping ‘score’ with ‘system’ as a reframing exercise to make it sound more intricate and elaborate (and worth your investment). In addition, Alchemer, an enterprise survey platform company, recently attempted to “bring NPS to life.” But sorry to say, it looks to be on life support. And no miracle can resurrect NPS’s lifeless body, no matter how hard we pray (or how much more money we offer to the brand gods).

It's Time for a Fresh Approach

Our team at Apex, inspired by the deficiencies of NPS, went back to the drawing board to figure out this core question, “How do your customers really feel about your brand?” Why? Because our behavioral science roots tell us it’s the attitudes people hold that guide their actions.

We began with fundamental principles of behavioral science and psychology. And we let evidence and science be our guide. No religion or Hail Marys here. Where NPS falls short, Apex seeks to go the distance. And let’s be clear; we’re not throwing out the baby with the bathwater. NPS, on its own, is misleading. But if you add the layers of business-wise behavioral science and AI-based intelligence reporting, it can transform into something of value for researchers.

Like NPS, Apex keeps things simple. It has been purpose-built to create an NPS-like score, but that’s where the comparisons end. Unlike NPS, Apex explains the “why” of the number and guides brands on where to take action to improve their score in the future. It also comes with rich insight and delivers every business’s needs from a brand health metric.